I make a big deal about getting kids to think, not merely remember.

But, yes, sometimes we do simply need to memorize a bunch of information.

After all, we cannot think about information that we’re struggling to recall.

Memorizing is indeed an essential tool for thinking.

But I always went about it wrong. In fact, I was awful at helping students to memorize. No one ever taught me how to do it!

So, here are some things to know about memorizing:

- We remember things that we think about. So, to memorize, you’ll need to apply, analyze, evaluate, etc.

- We can remember more when we “chunk” related material. So, to memorize, don’t study isolated information. Form connections.

- We remember things that are unusual. So make those connections weird, unexpected, and even a little PG-13!

- We remember things that we’ve consistently revisited over long periods of time. So review your connections on a regular basis until they’re in your long term memory.

Let’s start by looking at how we can “chunk” information.

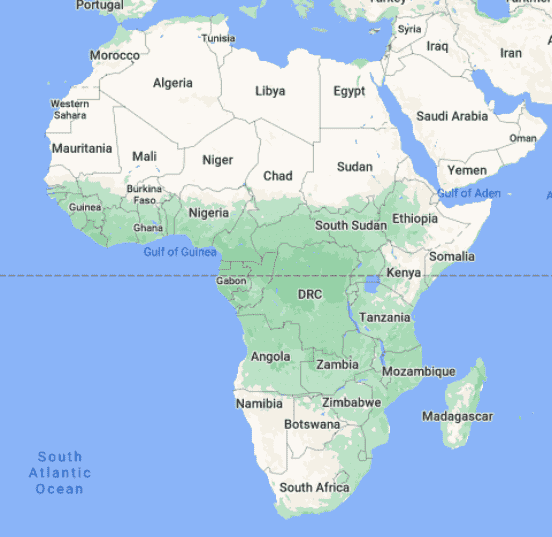

The Map of Africa

I grew up with the game/TV show _Where In The World Is Carmen Sandiego?_. The game show had an amazing theme song. In each episode’s final challenge, the contestant had to fill in a continent’s map with the correct countries within a time limit.

9-year-old Ian knew the pattern. Kids who got a map of Africa were toast. Rarely did a contestant know the layout of Africa well enough to win (well, this kid did it!).

And, even as a grown-up, my knowledge of African geography is embarrassingly weak. So, let’s use the map of Africa as an example of how I could better memorize information.

Chunk It!

We can only hold seven to ten pieces of information in our working memory. Sounds limiting right!? But, we can combine small pieces of information into larger chunks. Then we can squeeze more information into those 7 to 10 spots.

There’s no better example of “chunking” than phone numbers. You can remember 867-5309 much easier than 8675309, even though it’s the same set of digits. Our brains store 867-5309 as just two chunks, whereas 8675309 is seven separate pieces.

If you can recall the opening of the Gettysburg Address, you haven’t memorized individual letters. You’re not remembering single sounds. You store words! Words are chunks. You also remember groups of words. If you can remember “Four score and seven…” you’ll know that “years ago” comes next. In fact, that entire phrase can become one single chunk. The whole thing occupies only one of your 7 to 10 memory slots.

So our limited number of memory spots can each hold larger amounts of information when we chunk related information together. So, when we want students to memorize, we can’t give them unconnected bits of information. We have to chunk information into larger groups.

Chunking Africa

Let’s look at our map of Africa. There are a lot of countries. I’d never be able to just “memorize the map.” So let’s chunk it! I’d start with the top row. We have Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt.

I think that Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia are a good chunk. I could definitely store those three countries as one unit. If I wanted to, I could remember “MAT” as a clue. I think immediately of a high school friend named Matt. Personal connections will improve memory!

And I happen to already know that Egypt is over there in the east. That’s already in my long-term memory from other experiences. So then, how will I remember that Libya is in between MAT and Egypt? To me, the word “Libya” reminds me of “library”.

Oh, I also know that Tunisia is where they filmed the desert scenes in Star Wars.

Want to Remember? Then Think!

I’m already improving my memory because I’m thinking a lot about the positions of these countries. My brain isn’t just looking at isolated information. I’m creating connections. That by itself will help me to remember. You remember what you think about.

You’ll note that I’m creating “mnemonics” or memorable connections. Our brains are quite bad at remembering individual facts but amazing at recalling connections, stories, or jingles. I mean, I can perfectly remember certain commercials from my childhood because they were presented as catchy songs or funny rhymes.

We Remember Unusual Things

So, here’s a little memory story about those countries.

“Harrison Ford and my friend Matt landed in Morocco, walked through Algeria, and then filmed Star Wars in Tunisia. They checked out a book at the library in Librya at the pyramids, which they visited in Egypt before flying home.

That’s a story I’ll remember! I can picture it all in my mind’s eye. And note that I go from west to east since I naturally read left to right. I’ll do that consistently as I memorize the countries.

Move It To Long-Term Storage

I hear you. You’re thinking: Wait. So I have to have a whole story for every single thing I want to remember?

No! Because over time, my brain will eventually file the information into my long-term memory. I won’t need the story. I’ll just know it!

That’s the job of a mnemonic. They help us remember information long enough to get it locked away. A mnemonic moves information from short-term into long-term memory. Now, you’ll need to revisit that mnemonic. But you can read more about how periodic reviews are essential to building long-term memory here.

Next Row!

I’m feeling good about that first chunk of countries. What about the next row?

We’ve got the following countries along with the immediate connections my brain made

- Western Sahara – this is a disputed region which already makes it more memorable for me.

- Mauritania – the name sounds like Mary (my wife) and Tanya (which reminds me of Tanya Harding)

- Mali – reminds me of Bali, a place where I drank straight from a coconut

- Niger – reminds me of the name Nigel but also a tiger? Maybe it’s Nigel the tiger.

- Chad – makes me think of a kid I knew growing up

- Sudan – “sue Dan” makes me think of filing a lawsuit against my former student, Dan, who was quite memorable.

- Eritrea – reminds me of Atreyu from The Never Ending Story

So, you’ll note that mnemonics are highly personal. You and I won’t have the same ideas. In fact, my mnemonic is probably useless to you because our experiences are so different. I’ll tell you my memory story, anyway! Going west to east:

I arrived in the disputed land of Western Sahara and picked up Mary and Tanya Harding. We all ate drank from a coconut in Bali with Nigel the Tiger. Then we saw Chad. Chad was sad because he had to sue Dan. And I said, Chad you’re not as sad as Atreyu was when his horse died in The NeverEnding Story !

Bonkers, right? But it’ll work! Especially if I retell it tonight. And then see if I can recall the story tomorrow. Combine it with my Harrison Ford story, and we’ve already got a dozen African countries memorized.

I won’t do the whole continent, but you can see how powerful (and fun) this technique is. I’ve already got 11 countries crammed into two little stories.

Let’s see how chunking and mnemonics are helping me learn to read Japanese.

Reading Japanese

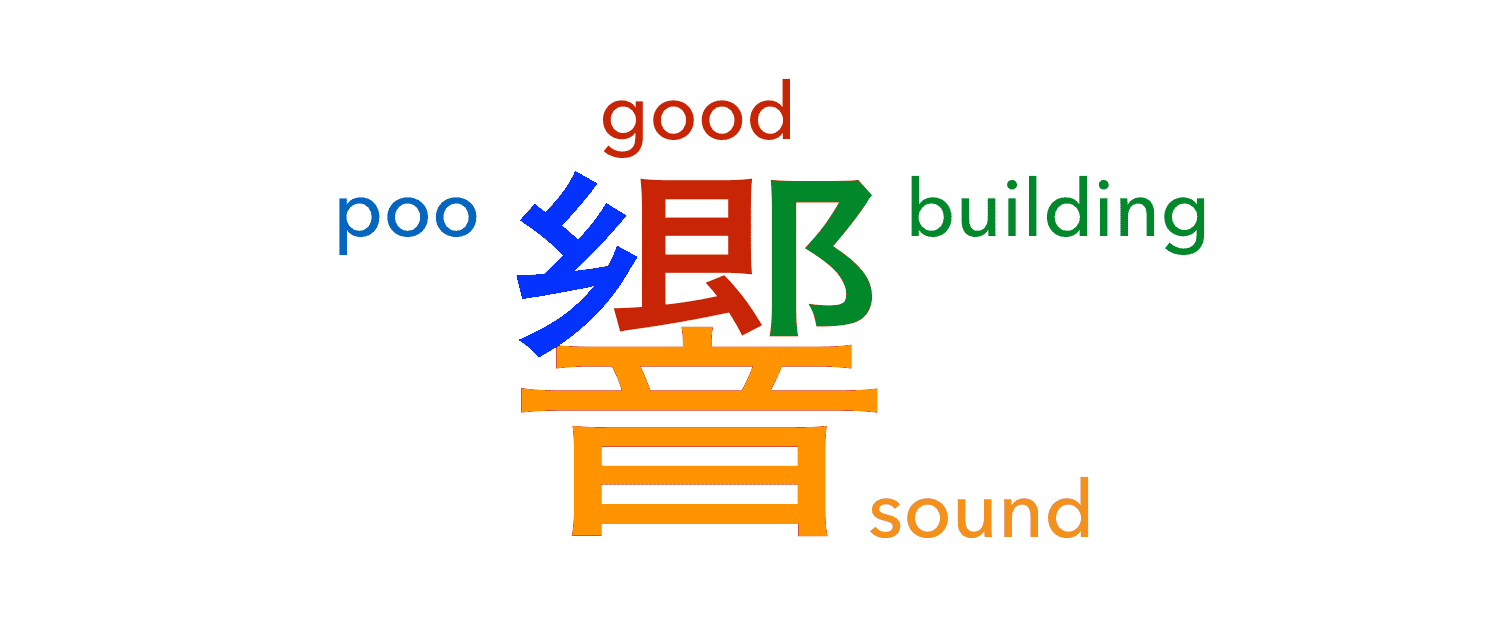

So, I’ve been working on memorizing kanji, a Japanese writing system built on thousands of characters. I need to memorize ~2,000 to have a high school level of literacy. And they have multiple meanings, multiple readings, and some require dozens of pen strokes to write.

But, by chunking, using mnemonics, and reviewing on a schedule, I’ve memorized over 800 characters in 18 months. During a pandemic. While running a business. And raising a toddler. (I use the pre-created program WaniKani to help.)

Now, the character 響 looks impossible to remember, right? It’s pure chaos. It takes 20 pen strokes to write it out.

But, I can use chunking to make sense of it right away. Because of some prior knowledge, I see that 響 is built out of four simpler symbols. Those chunks are already stored away in my long-term memory from earlier mnemonics. The smaller symbols are poo (yes), good, building, and sound.

Put them together to get 響 which means “echo.”

Now, can you think of a way to remember that “poo”, “good”, “building”, and “sound” combine to make “echo”?

I mean, it’s kinda hard not to think of a story, right?

A poo that’s always been good suddenly smacks into a building and makes a sound that echoes!

Now, I also have to remember the character’s pronunciation. It’s “kyou” (rhymes with “no”). That’s easy. The poo hit the building in Kyoto, the former capital of Japan.

So, honestly, 響 is a super easy character for me to memorize since the mnemonic is so vivid. I’m not at all bothered by the fact that it takes 20 strokes to write. To me, it’s just four memorable chunks with a very very funny story.

Now, I’m also juggling literally thousands of other characters and vocabulary words, so I need to review this character periodically. But, since this one has a great story, it won’t take too many reviews before it’s stored away for good!

Memorizing A Deck of Cards

You can make a memorable mnemonic no matter how dull the information may seem. Here’s US memory champ Ron White explaining how he can memorize a deck of 52 cards in 90 seconds.

There’s no magic. He just tells himself a weird story about all 52 cards. He makes a giant mnemonic!

To Remember: Chunk, Create Stories, and Repeat

If we want students to remember the material we teach, we have to set them up for success. Chunk related information together. Turn it into a story. Even better, let your students create their own, personal mnemonics for tricky information. And then review. Come back to those wacky stories quickly and often until the information makes its way into your kids’ long-term memory.