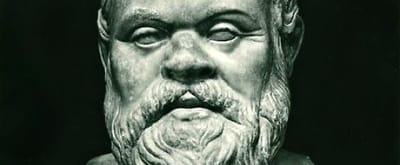

Socrate. Photo by Domenico Anderson.

As my students learn about Socrates, countless avenues of discussion open up. Time does not permit a deep enough study, so here are three raw ideas inspired by Socrates. Please feel free to take them and embellish.

Taking A Stand

My class recreated the painting The Death of Socrates for our school’s Pageant of the Masters-style production.

Death Of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David

In the painting, we see the final moments of Socrates’ life as he grasps the cup of hemlock. He could have easily escaped prison, but chose to stand by his convictions and chose death by poison.

Big Questions:

- Is it right for Socrates to chose death to stand up for his beliefs?

- What are the effects of such a sacrifice?

- What would be the effects of choosing to escape and survive?

- Which would lead to the greater good?

The Truth of History

Socrates’ life is a mystery. He is only known through his student Plato’s writing.

First, this leads to a fun discussion. We imagine a student carrying on my teachings after my death, writing and discussing my ideas. I’m sure you know the one in your class that makes this situation funny.

But then (if you’re brave), ask your students to think of two different ways to portray you, from two different points of view. Neither has to be a negative.

Which is correct?

This opens up the concept of questioning Plato’s written history. How do we know the accuracy of Plato’s writings? Was he even trying to be completely accurate, or was he using Socrates as character to prove a point? Do we really know anything about Socrates?

Make the question larger and more abstract: How we can trust history?

The Power Of Questions

Finally, Socrates is famous for his Socratic Method. It has frustrated and enlightened students for centuries. A question is only answered with another question.

Socrates engaged in questioning of his students in an unending search for truth. He sought to get to the foundations of his students’ and colleagues’ views by asking continual questions until a contradiction was exposed, thus proving the fallacy of the initial assumption.

From University of Chicago’s Law School

Ask your students to think about the power of questions:

- Which is more powerful, a question or an answer?

- What questions might have led to (The American Revolution, Women’s Rights, The Internet).

- What everyday activity can you question?

Let me know what you come up with! Please email me at ian@byrdseed.com or on Twitter at @IanAByrd.